EU Publishes General-Purpose AI Code of Practice

Everything you need to know about the GPAI Code of Practice | Edition #22

Hey 👋

I’m Oliver Patel, author and creator of Enterprise AI Governance.

This free newsletter delivers practical, actionable, and timely insights for AI governance professionals.

My goal is simple: to empower you to understand, implement, and master AI governance.

If you haven’t already, sign up below and share it with your colleagues. Thank you!

After months of intense negotiation involving hundreds of experts, the final version of the General-Purpose AI (GPAI) Code of Practice has been published by the European Commission. If deemed adequate, it will be formally approved via an implementing act in the coming weeks or months.

The GPAI Code of Practice consists of three separate chapters, on transparency, copyright, and safety and security, each of which is summarised below.

This week’s newsletter is a comprehensive guide to the GPAI Code of Practice. It covers:

✅ What are the obligations of providers of GPAI models?

✅ What is the GPAI Code of Practice?

✅ What’s happened so far?

✅ What happens next?

✅ The Transparency Chapter

✅ The Copyright Chapter

✅ The Safety and Security Chapter

✅ Appendix. Model Documentation Form

What are the obligations of providers of GPAI models?

You cannot understand the GPAI Code of Practice without understanding the associated provisions in the AI Act.

The AI Act defines GPAI models as AI models which display “significant generality and are capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks”. Providers are organisations or entities that develop such AI models and place them on the market or otherwise make them available.

These models, which are commonly referred to as foundation models, dominate modern AI, in terms of both industry and consumer use, as well as research, development, and investment. It is no exaggeration to say that the generative AI boom of the past few years has been driven by advances in GPAI model capabilities, the corresponding democratisation and consumption of these models, and the increasingly mainstream applications they power.

Interestingly, the first draft of the AI Act, published by the European Commission in April 2021, was near silent on the question of how to govern GPAI. This became a totemic issue during the trilogue negotiations, with intense disagreement between the Council, Commission, and Parliament on this defining question.

It was recognised that although GPAI models are the (current) AI technology with the potential to have the most significant impact on society, their development and adoption is also critical for Europe’s future economic competitiveness, productivity, and ability to innovate.

Eventually, an agreement was reached. The compromise position is enshrined in EU law, in Articles 53, 54, and 55 of the AI Act, which outline the obligations of providers of GPAI models and providers of GPAI models with systemic risk.

Here is a summary of these obligations:

There are specific obligations for providers of all GPAI models, as well as additional obligations for providers of GPAI models with systemic risk.

Providers of GPAI models must develop and maintain comprehensive technical documentation which provides information about the GPAI model, how it was developed, and how it should be used.

Some of this information must be shared with the EU AI Office and/ or national regulators (on request), and some must be proactively shared with ‘downstream providers’, which are organisations that integrate GPAI models into an AI system.

Providers must also produce and make publicly available a detailed summary of the content and data used to train the GPAI model.

Finally, providers must implement a policy to comply with EU copyright and intellectual property law.

Providers of GPAI models with systemic risk must comply with all the above obligations (outlined in Article 53), as well as a suite of additional obligations (outlined in Article 55). This includes to:

notify the AI Office about GPAI models with systemic risks;

perform model evaluations (e.g., adversarial testing and red teaming);

proactively assess and mitigate systemic risks;

track, document, and report serious incidents; and

ensure an adequate level of cybersecurity protection, to mitigate systemic risks.

There are important exemptions for providers of open-source GPAI models. For example, they do not need to publish and maintain the technical documentation mentioned above. However, providers of open-source models with systemic risk must comply with all the above obligations.

Crucially, the above obligations are applicable from 2 August 2025.

What is the GPAI Code of Practice?

The GPAI Code of Practice was published by the European Commission on 10 July 2025. However, it has not yet been formally approved by the EU.

In EU law, a code of practice is a voluntary tool which helps organisations comply with specific regulatory or legal obligations. Although an organisation is not obliged to adopt and follow an EU code of practice, doing so can offer useful guidance and provide a standardised approach or templates for regulatory compliance. It can also provide more legal certainty regarding the validity of the compliance approach taken, given that codes of practice are formally endorsed and approved by the EU via implementing acts.

Ultimately, codes of practice are designed to make life easier, by helping organisations and regulators navigate a complex and important area of law. However, you can still be compliant even if you do not sign up to and follow a code of practice.

Article 56 of the AI Act stipulates that the AI Office must encourage and facilitate work to develop GPAI model codes of practice, to support AI Act compliance. This explicitly mandates that the codes of practice should address the specific provisions outlined above, and that they should be developed in a multi-stakeholder forum involving GPAI model providers, downstream providers, national regulators, civil society, industry, academia, and other relevant stakeholders.

The GPAI Code of Practice was not developed or written by the EU institutions or EU policymakers. Rather, it is the result of a large joint effort among many external experts and stakeholders. According to the EU, 13 independent expert chairs led the drafting process, and they incorporated over 1,600 written submissions and feedback from 40 workshops.

What’s happened so far?

1 August 2024: EU AI Act enters into force. It contains specific obligations for providers of GPAI models, as well as corresponding provisions requiring GPAI codes of practice to be developed.

30 July 2024: AI Office launches public consultation and call for expression of interest to participate in GPAI Code of Practice development.

30 September 2024: AI Office kicks off the work to develop the GPAI Code of Practice, with an online plenary attended by nearly 1,000 experts.

14 November 2024: First draft of the GPAI Code of Practice published.

19 December 2024: Second draft of the GPAI Code of Practice published.

11 March 2025: Third draft of the GPAI Code of Practice published.

2 May 2025: The AI Act deadline for the GPAI codes of practice being ready and available. The final version was published after the deadline.

10 July 2025: Final version of the GPAI Code of Practice shared with the Commission and published.

What happens next?

The ball is now in the European Commission’s court.

Now that the GPAI Code of Practice has been finalised and published, it is to be assessed by the Commission and Member State representatives. If deemed adequate, the Code can then be formally approved and adopted via an EU implementing act. This would render it valid as an instrument to demonstrate compliance with the AI Act (although it does not guarantee compliance).

For the privacy gurus reading, this adequacy decision is the same type of legal instrument as the ‘adequacy decision’ which the EU issues in order to allow unrestricted personal data transfers from the EU to a third country.

Given the timelines, it is highly unlikely that the Code will be approved in time for the 2 August 2025 compliance deadline. This has contributed to and fueled intense discussion and lobbying regarding delaying the AI Act. However, a delay looks dead in the water, after a European Commission spokesperson recently said: "Let me be as clear as possible, there is no stop the clock. There is no grace period. There is no pause."

However, the Commission has confirmed that there will be flexibility for organisations that sign up and adhere to the GPAI Code of Practice. In the first year, from 2 August 2025 to 1 August 2026, the signatory organisations will be assumed to be acting in good faith and will not face enforcement action, even if they are not yet fully compliant with all relevant provisions. It is implied by omission that this flexibility will not be afforded to providers of GPAI models who have not signed up to the GPAI Code of Practice.

Therefore, even if the GPAI Code of Practice is ultimately approved via an implementing act, no organisation is obliged to follow it, and it does not create any new legal obligations on top of the AI Act. However, there is now an extra incentive for organisations to sign up to it, as they are to be treated in a more flexible way for the first year, thereby benefiting from a de facto grace period. At the time of writing, some AI companies, including OpenAI and Mistral, have announced their intention to sign the GPAI Code of Practice.

Another key point is that although the obligations for providers of GPAI models become applicable on 2 August 2025, providers have until 2 August 2027 to comply with these obligations for GPAI models that are already placed on the market (i.e., before 2 August 2025). Enforcement of these obligations will be led by the Commission’s AI Office, as opposed to national regulators.

Alongside these developments, the Commission is planning to publish guidelines on GPAI models, to provide further clarity on the above obligations. They will be analysed in this newsletter when available.

As MLex journalist Luca Bertuzzi highlights, some questions remain unanswered, such as whether organisations will be able to sign up to specific Code of Practice chapters (instead of the whole thing), as well as when the training data disclosure template will be published.

On the latter, and as you will see below, the published Code of Practice does not contain guidance on how organisations should produce and make publicly available a detailed summary of the content and data used to train their GPAI models. Although the chapters on transparency and copyright acknowledge that they are complementary to this, the finer details regarding how organisations should comply with this consequential obligation are being left to the AI Office.

The Transparency Chapter

Link: Code of Practice for GPAI Models - Transparency Chapter and Model Documentation Form

Chapter leads: Nuria Oliver and Rishi Bommasani

The first of three chapters focuses on the technical documentation which GPAI model providers are obliged to produce, maintain, and share with key stakeholders.

In particular, it provides practical guidance and a standardised approach for how providers of GPAI models should develop and maintain comprehensive technical documentation, which provides information about the GPAI model, how it was developed, and how it should and can be used. This is mandated by Article 53(1) (a) and (b), which stipulate the information which must be shared (by providers) with the AI Office and/or national regulators (in response to a lawful request), as well as the information which must be proactively shared with downstream providers.

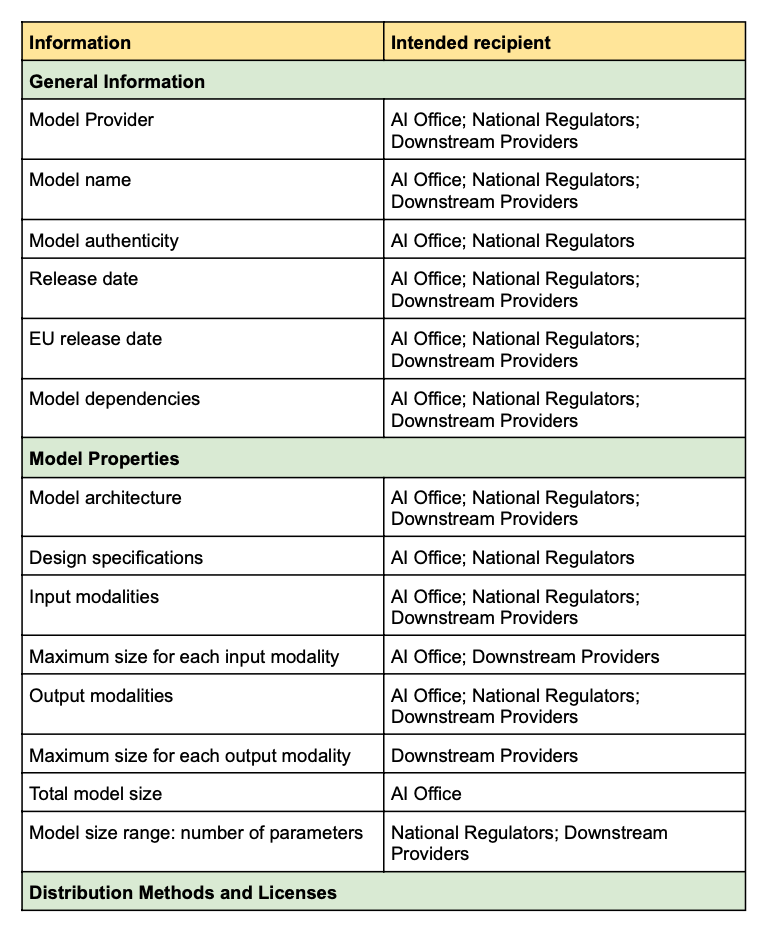

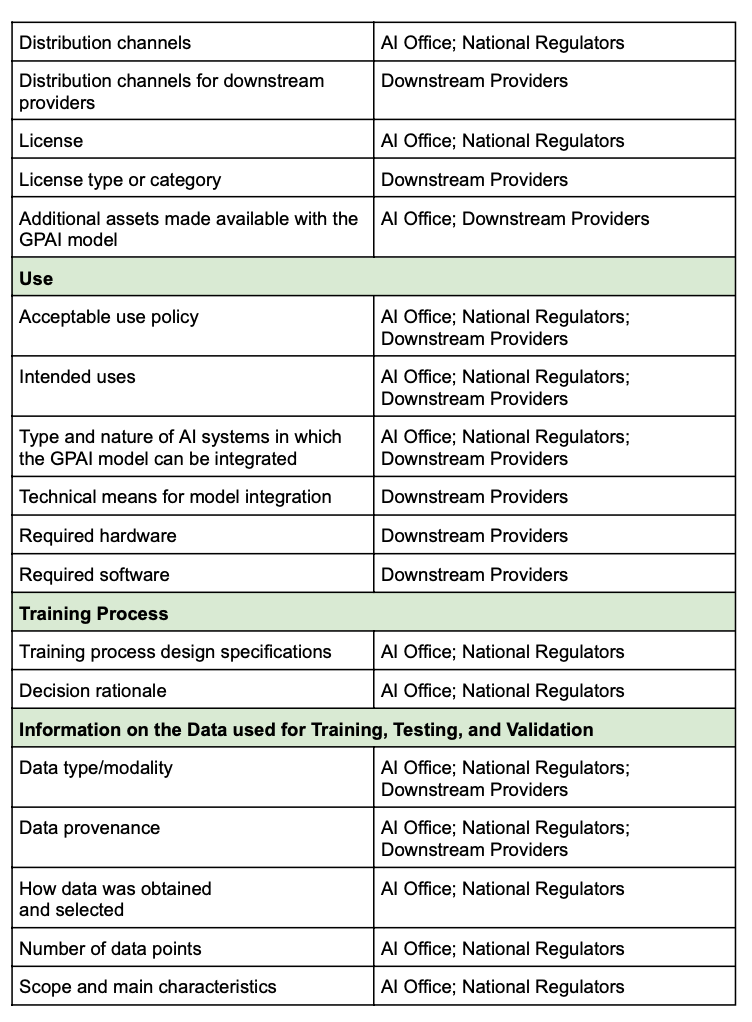

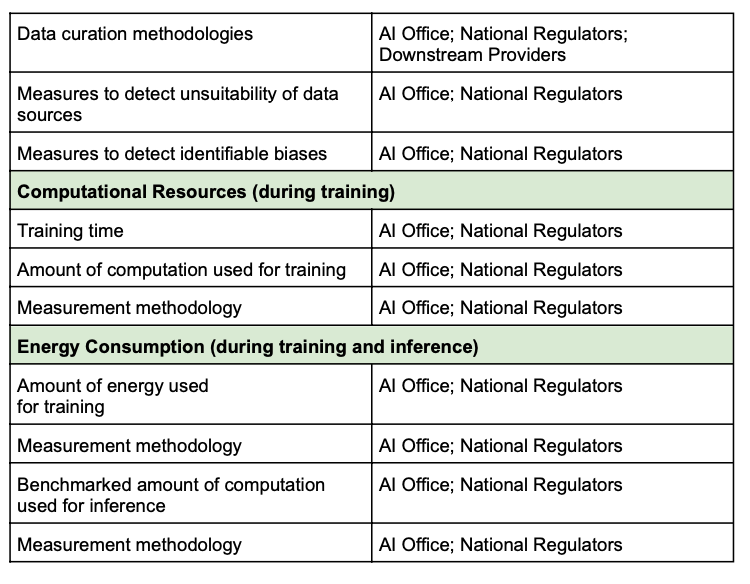

The key contribution of this chapter is a ‘Model Documentation Form’, which is a comprehensive and neatly-structured template which providers can use to ensure they gather and document all the information which they are required to maintain and potentially share with either the AI Office, national regulators, or downstream providers respectively. This information, which is listed across Annexes XI and XII of the AI Act, is now brought together in this handy tool.

See the Appendix below for a visual summary of the Model Documentation Form, which consists of 42 metadata attributes across 8 categories. The attributes include training time and computation, model size, energy consumption, data collection and curation methods, and input and output modalities.

Organisations which sign up to this chapter of the GPAI Code of Practice are committing to three transparency-related measures. These are:

Measure 1.1: Drawing up and keeping up-to-date model documentation.

Measure 1.2: Providing relevant information (i.e., in response to valid and lawful requests from the AI Office or national regulators, and proactively to downstream providers).

Measure 1.3: Ensuring quality, integrity, and security of this information.

The chapter repeatedly emphasises the importance and necessity of all stakeholders adhering to their confidentiality obligations under EU law

The Copyright Chapter

Link: Code of Practice for GPAI Models - Copyright Chapter

Chapter leads: Alexander Peukert and Céline Castets-Renard

The second chapter’s exclusive focus is on how organisations can comply with the obligation to implement a policy to comply with EU copyright and intellectual property law. This is mandated in Article 53(1)(c) of the AI Act. It applies to providers of all GPAI models and GPAI models with systemic risk, including open-source GPAI models.

The chapter clarifies that the most relevant EU copyright legal instruments for this policy are:

Copyright and Information Society Directive (2001/29/EC)

Copyright Directive ((EU) 2019/790)

Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights Directive (2004/48/EC)

In particular, the EU Copyright Directive includes two text and data mining (TDM) exceptions—one for scientific research and another that allows broader use (including for commercial purposes), unless the copyright holder opts out. The TDM exception could, in theory, apply to AI training.

Organisations which sign up to the Copyright Chapter of the GPAI Code of Practice are committing to five tangible measures. These are:

Measure 1.1: Draw up, keep up-to-date and implement a copyright policy.

This policy should be outlined in a single document, which is encouraged to be made publicly available (although this is not legally required).

Measure 1.2: Reproduce and extract only lawfully accessible copyright-protected content when crawling the World Wide Web.

This includes not using technological means to bypass controls which are intended to protect copyright-protected data from unauthorised scraping or access (e.g., paywalls).

Measure 1.3: Identify and comply with rights reservations when crawling the World Wide Web.

This includes using web crawlers which are designed to recognise and follow instructions which specify the copyright status of content.

Measure 1.4: Mitigate the risk of copyright-infringing outputs.

This includes implementing ‘technical safeguards’ to prevent GPAI models from reproducing their training content and prohibiting such copyright-infringing use in the acceptable use policies.

Measure 1.5: Designate a point of contact and enable the lodging of complaints.

This includes establishing a mechanism for affected rightsholders to pursue complaints and receive information in response.

The Safety and Security Chapter

Link: Code of Practice for GPAI Models - Safety and Security Chapter

Chapter leads: Matthias Samwald, Yoshua Bengio, Marietje Schaake, Marta Ziosi, Daniel Privitera, Anka Reuel, Alexander Zacherl, Nitarshan Rajkumar, and Markus Anderljung.

The third and final chapter is the longest and most detailed; significantly more so than the other two. Therefore, I will provide only a very high-level summary here, and explore it in more detail in a future newsletter post.

The Safety and Security Chapter focuses on the obligations for providers of GPAI models with systemic risk. It consists of ten concrete commitments (and dozens of encompassing measures), which organisations can sign up to. These ten commitments provide a robust gameplan and comprehensive structure for organisations seeking to comply with the full suite of obligations for GPAI models with systemic risk. They are:

Commitment 1: Adopt a Safety and Security Framework.

Commitment 2: Identify systemic risks stemming from the GPAI model.

Commitment 3: Analyse each identified systemic risk.

Commitment 4: Determine whether or not to accept the identified systemic risks.

Commitment 5: Implement safety mitigations along the GPAI model lifecycle.

Commitment 6: Implement security mitigations along the GPAI model lifecycle.

Commitment 7: Report information to the AI Office about the GPAI model’s safety and security, including risk assessment and mitigation.

Commitment 8: Allocate responsibility and ownership for systemic risks.

Commitment 9: Track, document, and report serious incidents.

Commitment 10: Document how this Chapter is implemented and adhered to.

Appendix. Model Documentation Form

Disclaimer: This Appendix provides a simplified, visual summary of the Model Documentation Form, which is part of the Transparency Chapter of the GPAI Code of Practice. Its purpose is to provide a digestible snapshot of the 42 metadata attributes and 8 categories, to enable ease of understanding for readers.

Click here to download the EU’s official editable word document version of the Model Documentation Form and to view the content in full. Full credit for the below content goes to the original authors of the GPAI Code of Practice Transparency chapter.

This was a great summary. Thanks for sharing.

If a provider of a high-risk AI system embeds a GPAI model/system into their AI system, are they responsible for ensuring that GPAI model meets the data & data governance requirements of Article 10?