Debunking 10 Common EU AI Act Misconceptions (part 1)

AI Act myth-busting to support your compliance | Edition #16

Hey 👋

I’m Oliver Patel, author and creator of Enterprise AI Governance.

This free newsletter delivers practical, actionable, and timely insights for AI governance professionals.

My goal is simple: to empower you to understand, implement, and master AI governance.

If you haven’t already, sign up below and share it with your colleagues. Thank you!

The EU AI Act entered into force in August 2024 and its first provisions became applicable in February 2025.

Due to a combination of factors, such as the complexity and novelty of the law, and the lack of guidance and standards, some unhelpful misconceptions have taken hold.

This two-part series on Enterprise AI Governance presents and debunks 10 common misconceptions about the AI Act, providing a detailed explanation for each one. The first 5 are covered in part 1 and the second 5 will be covered in part 2.

The ten misconceptions are:

The EU AI Act has a two-year grace period and applies in full from August 2026.

All open-source AI systems and models are exempt from the EU AI Act.

High-risk AI models are explicitly regulated under the EU AI Act.

Emotion recognition is prohibited under the EU AI Act.

Facial recognition is prohibited under the EU AI Act.

Transparency is required for ‘limited risk’ AI systems.

Third-party conformity assessments are required for all high-risk AI systems.

Fundamental rights impact assessments are required for all high-risk AI systems.

All high-risk AI systems must be registered in the public EU-wide database.

Deployers do not need to register their use of high-risk AI systems.

Misconception 1: The EU AI Act has a two-year grace period and applies in full from August 2026

It is commonly remarked that the EU AI Act has a two-year grace period, which allows organisations to prepare to be compliant. Although there are grace periods for compliance, they vary in length, and certain provisions are already applicable today.

In fairness, Article 113 does state that the AI Act “shall apply from 2 August 2026”. However, given the number of exceptions to this, simply claiming there is a ‘two-year grace period’ is misleading.

The reality is that different provisions become applicable at different times. Although most provisions apply from August 2026, the provisions on AI literacy and prohibited AI practices became applicable in February 2025, and the obligations for providers of new general-purpose AI models become applicable in August 2025.

Here is a breakdown of when the most significant provisions apply:

2 February 2025: prohibition of specific AI practices became applicable.

2 February 2025: AI literacy provisions (for deployers and providers of AI systems) became applicable.

2 August 2025: obligations for providers of ‘new’ general-purpose AI models become applicable (i.e., general-purpose AI models placed on the market from 2 August 2025 onwards).

2 August 2026: many of the AI Act’s provisions become applicable, including obligations and requirements for high-risk AI systems listed in Annex III.

2 August 2027: obligations and requirements for high-risk AI systems which are products, or safety components of products, regulated by specific EU product safety laws (listed in Annex I) become applicable.

2 August 2027: obligations for providers of ‘old’ general-purpose AI models become applicable (i.e., general-purpose AI models placed on the market before 2 August 2025).

Although the provisions on prohibited AI practices became applicable earlier this year, meaningful enforcement will come later. This is because the applicability of the penalty and governance regime, including the deadline for member states to designate their AI regulators, lands on 2 August 2025. This creates a unique situation where there is a 6-month lag between important provisions becoming applicable and the regulatory enforcement structure and regime being operational.

Misconception 2: All open-source AI systems and models are exempt from the EU AI Act

Although there are broad exemptions for open-source AI systems and models, there are also several important ways in which the AI Act regulates them.

For example, high-risk AI systems which are open-source are still classified as high-risk, and providers of general-purpose AI models which are open-source must adhere to specific obligations (which are trimmed down in some cases).

Article 2(12) states that the AI Act “does not apply to AI systems released under free and open-source licenses, unless they are placed on the market or put into service as high-risk AI systems or as an AI system that falls under Article 5 or Article 50”. This has the following meaning:

Providers and deployers of high-risk AI systems which are open-source must adhere to all the obligations and requirements for high-risk AI systems, despite their AI system’s open-source nature.

The reference to Article 5 means that prohibited AI practices are prohibited, irrespective of whether or not they leverage open-source AI systems.

Finally, providers and deployers of open-source AI systems which interact with individuals, generate synthetic content and deep fakes, or perform emotion recognition or biometric categorisation, must adhere to the transparency obligations outlined in Article 50.

Article 53(2) refers to open-source AI models as “models that are released under a free and open-source licence that allows for the access, usage, modification, and distribution of the model, and whose parameters, including the weights, the information on the model architecture, and the information on model usage, are made publicly available”.

Providers of open-source general-purpose AI models must adhere to a limited set of obligations, such as publishing a summary of the model’s training data and implementing a copyright compliance policy.

However, providers of these models do not have to adhere to the obligations to produce and make available technical documentation about their general-purpose AI model. Nor do they have to appoint an authorised representative in the EU if they are established in a third country.

For providers of open-source general-purpose AI models with systemic risk, the full and extensive set of obligations for general-purpose AI models with systemic risk applies. This includes all the above obligations, as well as performing model evaluations, systemic risk assessment and mitigation, and ensuring adequate cybersecurity protection.

In practice, this will mean that despite the broad exemptions for open-source AI, it is likely that providers of some of the most advanced and widely used open-source AI models will have extensive compliance obligations.

Misconception 3: High-risk AI models are explicitly regulated under the EU AI Act

The AI Act regulates the following types of AI, with explicit and targeted provisions:

prohibited AI practices;

high-risk AI systems;

general-purpose AI models;

general-purpose AI models with systemic risk; and

certain AI systems which require transparency.

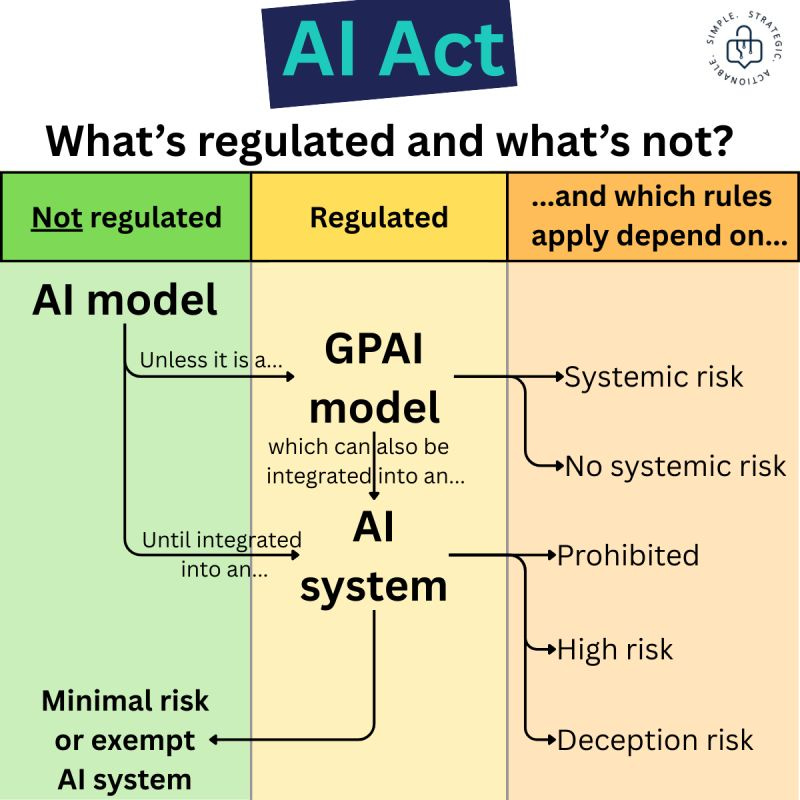

The AI Act does not explicitly refer to ‘high-risk AI models’ as a regulated category, nor are there specific provisions relating directly to them. Moreover, there are no specific provisions relating to AI models which are not general-purpose AI models.

This means that unless an AI model is general-purpose, or part of an AI system or practice which is high-risk, transparency requiring, or prohibited, it is not in scope of the AI Act.

However, in most scenarios, an AI model (or AI models) will be one of the most important components of a broader AI system, which could either be high-risk or used for a prohibited practice. Therefore, AI models are regulated in this ‘indirect’ but consequential sense.

Image credit: This helpful infographic from the team at Digiphile highlights what is and what is not regulated under the AI Act.

Interestingly, the AI Act does not include a legal definition of the term ‘AI model’.

Article 3 lists 68 different definitions, for terms like ‘AI system’, ‘training data’, and ‘general-purpose AI model’ (see below). Despite there being a definition of an important and common type of AI model (i.e., a general-purpose one), there is no definition of an ‘AI model’ itself, which is a broader and arguably more important and foundational concept.

In my view, given the centrality of AI models to high-risk AI systems, general-purpose AI models, virtually any type of prohibited AI practice, and the wider field of AI, it would have been helpful for the AI Act to include an official legal definition of an AI model.

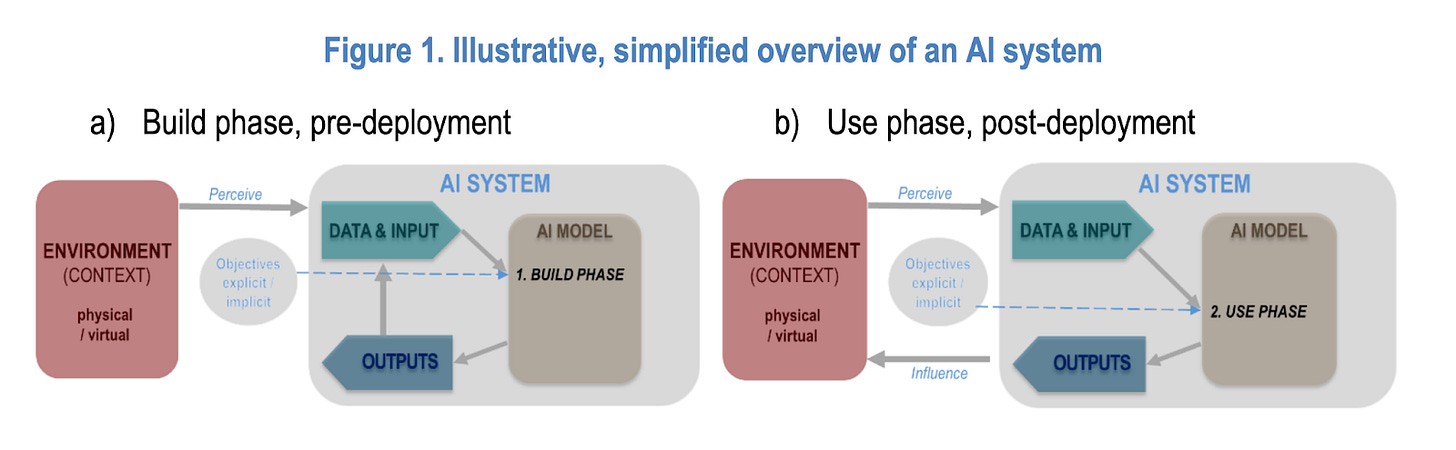

For context, the AI Act defines an AI system as: “a machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments”.

A general-purpose AI model is defined as: “an AI model, including where such an AI model is trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications, except AI models that are used for research, development or prototyping activities before they are placed on the market”.

The concept of an AI model has been defined in other sources.

NIST defines an AI model as: “a component of an information system that implements AI technology and uses computational, statistical, or machine-learning techniques to produce outputs from a given set of inputs”.

In its paper on the updated definition of an AI system, the OECD refers to an AI model as “a core component of an AI system used to make inferences from inputs to produce outputs”.

Image credit: OECD visual on the definition of an AI system, which highlights that an AI model is an essential component of an AI system.

Misconception 4: Emotion recognition is prohibited under the EU AI Act

Article 5(1) stipulates that the following AI practice is prohibited: placing on the market, putting into service, or using “AI systems to infer emotions of a natural person in the areas of workplace and education institutions, except where the use of the AI system is intended to be put in place or into the market for medical or safety reasons”.

This means that the use of AI-enabled emotion recognition is only prohibited in specific, pre-defined contexts; namely, the workplace and educational institutions.

It also means that AI-enabled emotion recognition could potentially be lawfully used in workplace and educational settings, if it can be demonstrated that this supports medical or safety objectives.

For example, using AI to infer and predict the emotional state of a pilot while they are flying a plane, for the sole purpose of determining the pilot’s future bonus or compensation package, would almost certainly be prohibited. However, if the AI system is used solely to initiate safety-critical interventions, which could prevent potentially harmful incidents, then this would likely be permitted under the AI Act.

Furthermore, AI systems used for emotion recognition in settings other than the workplace and educational institutions are classified as high-risk, not prohibited. This is clarified in Annex III(1), which lists high-risk AI systems and includes “AI systems intended to be used for emotion recognition”.

This means that providers and deployers developing, making available, or using emotion recognition systems in contexts other than the workplace and educational institutions, as well as emotion recognition systems for safety or medical reasons in the two aforementioned settings, must adhere to the obligations and requirements for high-risk AI systems.

To understand exactly what constitutes an emotion recognition system (that could either be high-risk or prohibited, depending on the context), we need to consult the definition provided in Article 3(39): “‘an AI system for the purpose of identifying or inferring emotions or intentions of natural persons on the basis of their biometric data”.

In practice, this implies that unless it is based on biometric data (e.g., voice or facial expressions), using AI for emotional recognition would not be classified as high-risk or prohibited, and thus may not even be in scope of the AI Act.

For example, if I copy and paste a colleague’s email into a generative AI tool, in advance of an important meeting, and ask it to predict their emotional state at the time of writing, this would most likely not be considered a prohibited AI practice entailing a hefty penalty, given the lack of biometric data being processed. However, if this was done via an AI assessing a video recording of a meeting in which their camera was on, the situation could be quite different.

European Commission guidelines on the topic have confirmed that an AI system inferring emotions from written text (i.e., content/sentiment analysis) is not prohibited as it does not constitute emotion recognition, because it is not based on biometric data.

Misconception 5: Facial recognition is prohibited under the EU AI Act

Similarly, there is no blanket prohibition on the development and use of facial recognition systems, which are already widely deployed in society.

However, there are prohibitions on the ways in which law enforcement can use facial recognition and similar technologies to perform remote biometric identification of people in real-time.

Also, if facial recognition technology was used for a prohibited AI practice, this would still be prohibited. However, this does not amount to a blanket prohibition.

Concretely, law enforcement use of ‘real-time’ remote biometric identification systems in public (e.g., facial recognition used to identify and stop flagged people in public) is prohibited, apart from in specific and narrowly defined scenarios.

Acceptable scenarios for law enforcement use of such technology includes searching for victims of serious crime, preventing imminent threats to life (e.g., terrorist attacks), and locating suspects or perpetrators of serious crimes (e.g., murder).

Before AI is used in this way, independent judicial or administrative authorisation must be granted. Also, the use can only occur for a limited time period, with safeguards to protect privacy and fundamental rights.

This became a totemic issue during the AI Act trilogue negotiations and legislative process. The European Parliament's initial AI Act proposals called for an outright ban on the use of real-time biometric identification systems in public, like facial recognition. This ban would have applied to law enforcement authorities and any other organisation, with no exceptions. The Council (EU member states) were never going to accept an outright prohibition and a compromise was brokered.

Some types of AI-enabled facial recognition, which are permitted, would be classified as a high-risk AI system.

Annex III(1) clarifies that ‘remote biometric identification systems’, ‘AI systems intended to be used for biometric categorisation’, and ‘AI systems intended to be used for emotion recognition’ are high-risk AI systems.

It is also conceivable that a facial recognition system or component could be used as part of any other high-risk AI system listed in the AI Act.

However, it is also conceivable that a facial recognition system or component could be part of an AI system which is not high-risk, nor in scope of the AI Act. This is because AI systems used for ‘biometric verification’, which perform the sole function of confirming or authenticating that an individual is who they claim to be, are not high-risk.

A facial recognition system used to unlock your phone would not be classified as high-risk, as it is merely confirming that you are who you claim to be (i.e., the owner of the phone). This is in contrast to live facial recognition cameras used by police to identify potential suspects from a crowd, as their facial data is being compared to a larger reference database of faces, with the goal of establishing a match.

Finally, as per Article 5(e), it is prohibited to use AI systems to conduct untargeted scraping of facial images, from the internet or CCTV footage, with the goal of creating or expanding databases which are used to develop or operate facial recognition systems. However, this does not prohibit the use of facial recognition in a broader sense, merely a specific data scraping practice.

Thank you, Oliver, for continuing to make sense of these important issues!

Thanks for sharing